Posted inMaterial Science

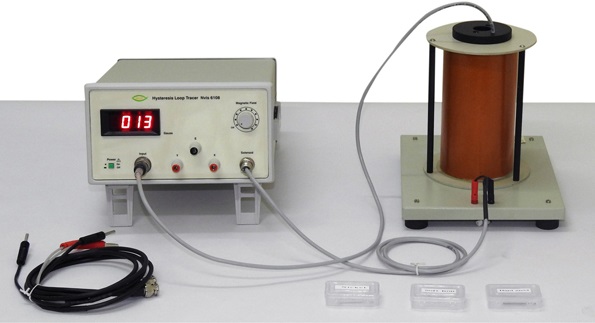

Magnetic Tapes

Magnetic tapes are extensively used for recording audio and video signals, although it is unclear how long this technology will continue to be used with the rising popularity of the digital versatile disk (DVD). Tapes can be made with either a particulate media adhered to a plastic substrate or a metal evaporated (ME) film on the substrate. The magnetic layer on a particulate tape is only 40% magnetic material whereas ME tapes have a 100% magnetic layer. Therefore, ME tapes give better quality recording, but they are more time consuming to produce and are more expensive. Particulate tapes are much cheaper and hence account for the majority of magnetic tapes.