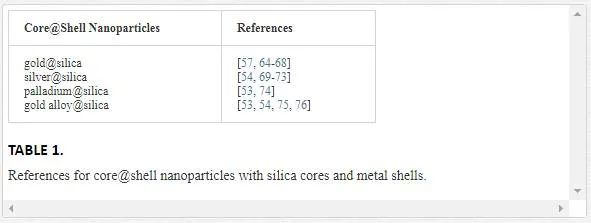

Metal nanoparticles (NPs) provide optical, magnetic, and electronic properties which are different from the corresponding bulk metal materials, leading to photothermal, therapeutic, and electronic device applications, respectively. Recent research efforts have explored NPs having complex compositions with controllable sizes and morphologies. Special attention has been given to metal NPs for use as optical materials (i.e., using palladium [1, 2], silver [3-12], copper [13-18], and particularly gold [19-31]). This is due to the ease of fabrication of these metal nanoparticles and their unique physical properties [32-34], such as the ability to absorb or scatter light [25, 35, 36]. However, the narrow scope of simple spherical metal NPs’ optical properties has limited their use in practical applications. Thus, investigators have pursued new classes of nanostructured materials such as triangular prisms [37-40], disks [41, 42], nanorods [43-46], nanocubes [47-51], and NPs coated with a shell (core@shell NPs) [52-58], to overcome the restrictions on the optical properties associated with simple spherical metal NPs. Among these, core@shell NPs represent a promising nanoscale tool for biomedical research [59-63]. A number of metals have been used as the shell for these NPs (as detailed in Table 1), but silica has proven to be the favorite core for such structures [64-76].

Recent research has also centered on the capacity of core@shell NPs containing metal/metal oxide cores to respond to an external stimulus (e.g., a magnetic field or near IR light) and to affect their local surroundings, resulting in their use in diagnostic, therapeutic, and drug delivery applications utilizing either a polymer coating or a more complex shell design [77-80]. The development of these more sophisticated NP structures has been presaged by a number of simpler particle architectures.

Types of Core@Shell nanoparticles

Core@shell NPs can be categorized according to their material properties (e.g., dielectric, semiconductor, etc.) and form (e.g., single-layered shell, multilayered shell, etc.). In this chapter, the core or shell materials in a core@shell NP are considered in terms of their constitution or shape. For this report, the core@shell NPs of interest are classified into three main groups: (i) silica@metal NPs; (ii) metal@silica NPs; and (iii) other forms of core@shell NPs.

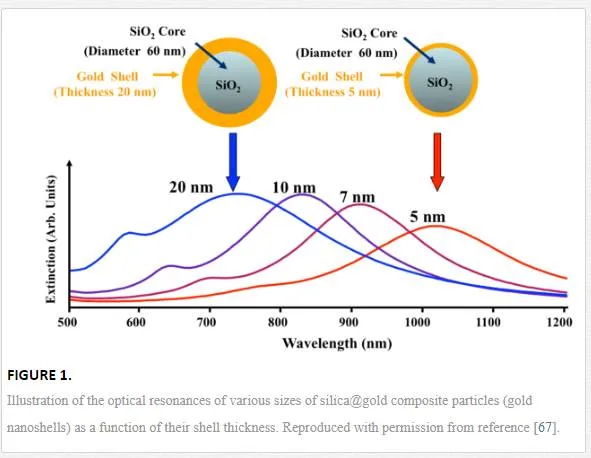

Silica@Metal Nanoparticles. Since the publication of the “Stöber Method” of preparing silica particles, various metals and metal oxide shell materials have been deposited on silica spheres [81]. Because of the unique qualities of gold, silica-based core@shell NPs with gold as the shell material became the focus of efforts to produce the first of these structures in the late 1990’s [64, 68, 82]. A gold coating on the silica core provides improved biocompatibility, photonic energy absorption, catalytic properties, chemical stability, bio-affinity (through greater diversity in the functionalization of the surface), and tunable optical properties [64]. Similar to the size-dependent color of pure gold NPs, the optical response of gold nanoshells (GNSs) depends dramatically on the relative size of the core NP as well as the thickness of the gold shell [67, 83]. Importantly, the surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) activity of GNSs can be increased or decreased by decreasing or increasing the thickness of the gold shell material [84, 85]. By adjusting the relative core size and shell thickness, an intense light absorption associated with the gold in the GNSs can be varied across a broad range of the optical spectrum, spanning the visible and the near-infrared spectral regions. This phenomenon is known as surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and its impact upon the extinction spectra of GNSs is illustrated in Figure 1 with regards to changes in shell thickness.

The development of these gold shells has been followed by a number of alternative metal and metal oxide coatings, broadening the number of applications for such core@shell structures [53, 54, 69, 74]. These data indirectly indicate that GNSs with a silica core (SiO2@Au NPs) may be useful for biomedical imaging, cancer treatment, and optical materials in future applications owing to the ability of certain wavelengths of light to penetrate human tissue.

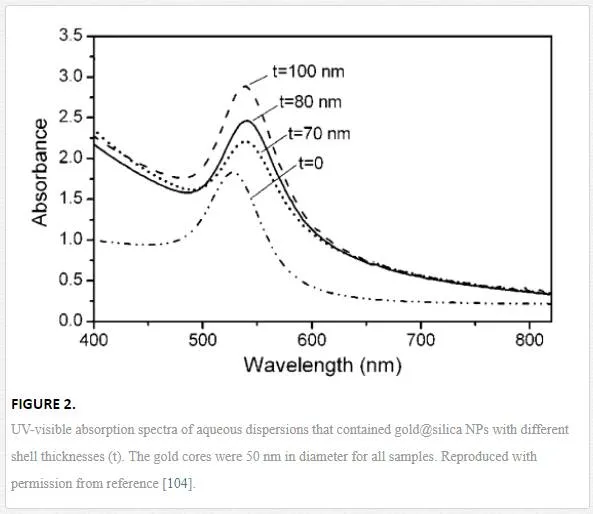

Metal@ Silica Nanoparticles. Using a silica coating as the shell on a metal core to form NPs with core@shell architectures offers several benefits. First, a silica shell diminishes the bulk metal conductivity and improves the chemical and physical stability of the core component [86]. Second, silica particles produced via the Stöber Method have been shown to be chemically biocompatible [87, 88]. And silica can be used to block the core surface from making contact with a biological environment without disrupting key phenomena involving the core surface, such as light absorption. This is an important feature for metals/metal oxides that have been shown to be cytotoxic. Third, the silica coating can be used to modulate the position and intensity of the surface plasmon absorption band due to both the optical transparency of silica at technologically important wavelengths of light and the shift in these bands associated with a small change in the metal’s optical properties because of the material in contact with their surfaces [89]. And the fourth point is that an outer silica shell on a metal nanoshell can help stabilize the metal shell when it is generating intense localized heat in response to intense light absorption [90, 91]. Therefore, scientists have recently focused more on silica coatings as a shell for a variety of core materials such as metals [92-99] and metal oxides [100-103], than on any other material. Many research groups have investigated the use of silica on coinage metals such as gold [92, 93] and silver [98]. Silica-coated gold or silver NPs are synthesized by using a slightly modified Stöber (or sol-gel) Method. The resulting coating does not interfere with the intensity of the light absorption for targeted wavelengths, and only produces a minor shift in the absorption band toward the higher wavelength region, as compared to an uncoated NP, as shown in Figure 2 [104]. This coating method has been adjusted further to control the uniformity of the thickness of the silica layer on gold NP cores [105].

Figure 2 provides the absorption spectra of aqueous dispersions of gold@silica (Au@SiO2) NP colloids with different shell thicknesses. The characteristic surface plasmon peak of the core of these NPs is ~528 nm before adding the silica coating to the gold cores. After coating with silica, the metal’s plasmon peak red-shifted to ~540 nm. This is because the refractive index of silica (n = 1.52) is slightly higher than that of water (n = 1.31), the solvent used to suspend the nanoparticles for collecting spectroscopic data [106]. The optical intensity of these Au@SiO2 NPs was increased correspondingly when thicker silica shells were created. But the specific positioning of this peak was not sensitive to the change in the silica coating thickness. In the report by Lu et al. referenced above, the silica-coated gold NPs were assembled into ordered arrays [104]. The transmission spectra collected from these lattices of Au@SiO2 NPs are shown in Figure 3. All samples were wet with the hollow spaces between NPs being completely filled with water, when these spectra were measured. The incident light was kept vertical to the (111) planes of these face-center-cubic lattices (Au).

Figure 2 provides the absorption spectra of aqueous dispersions of gold@silica (Au@SiO2) NP colloids with different shell thicknesses. The characteristic surface plasmon peak of the core of these NPs is ~528 nm before adding the silica coating to the gold cores. After coating with silica, the metal’s plasmon peak red-shifted to ~540 nm. This is because the refractive index of silica (n = 1.52) is slightly higher than that of water (n = 1.31), the solvent used to suspend the nanoparticles for collecting spectroscopic data [106]. The optical intensity of these Au@SiO2 NPs was increased correspondingly when thicker silica shells were created. But the specific positioning of this peak was not sensitive to the change in the silica coating thickness.In the report by Lu et al. referenced above, the silica-coated gold NPs were assembled into ordered arrays [104]. The transmission spectra collected from these lattices of Au@SiO2 NPs are shown in Figure 3. All samples were wet with the hollow spaces between NPs being completely filled with water, when these spectra were measured. The incident light was kept vertical to the (111) planes of these face-center-cubic lattices (Au).

These transmission spectra show two peaks resulted from the surface plasmon resonance of the gold core NPs around ~540 nm and the Bragg diffraction of each opaline lattice. Depending on the changes in the silica shell’s thickness, the position of the Bragg diffraction peak varied. For example, the Bragg diffraction peak overlapped with the surface plasmon resonance band when the silica shell was 70 nm in thickness, as shown Figure 3. In this case, only one broad absorption peak was observed at ~540 nm.

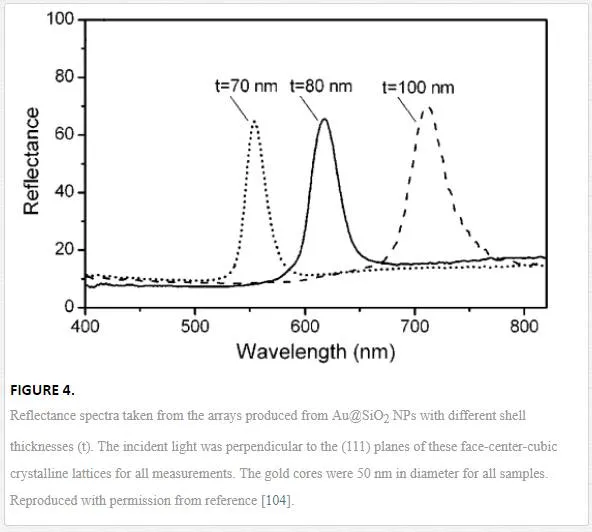

Figure 4 demonstrates the reflection spectra acquired from the surface array of Au@SiO2 NPs. All samples were wet with the hollow spaces between NPs being completely filled with water when these spectra were measured. The incident light was kept vertical to the (111) planes of these face-center-cubic lattices (Au).

For the reflectance spectra, the Bragg diffraction features were the only peaks detected, and they aligned with the features in the transmission spectra. Additionally, the peaks in Figure 4 associated with particles that possessed various shell thicknesses, were narrow and well-resolved. This shows that such core@shell nanoparticle arrays provide two pathways for modulating their interaction with light. Liz-Marzan et al. also recently illustrated the fabrication of 3D crystalline lattices from Au@SiO2 NP colloids; however, these authors failed to provide similar optical characterization [95]. Above all, the spectra displayed in Figures 2, 3, and 4 provide perspective regarding the potential for utilizing the optical properties of Au@SiO2 NP colloids, and their crystalline lattices.To tune the shell thickness from 20 to 100 nm, the experimental parameters (e.g., coating time and concentration of reactants, catalyst, or other precursors) can be precisely and systematically controlled. Li et al. demonstrated how the shell thickness for Ag@SiO2 NPs can be tuned by controlling certain parameters, the molar volume ratio of water to surfactant, R (R = [water]/[surfactant]), and the molar volume ratio of water to TEOS, H (H = [water]/[TEOS]) [98]. The manipulation of these parameters provides control over the availability of water molecules for the hydrolysis of TEOS (tetraethyl othosilicate).

Other researchers have developed the magnetic properties of alternative silica-coated cores (e.g., Fe, Ni, Co, and alloyed metal compounds) to be used in the presence of external magnetic fields for the improvement of bio-imaging, biological labeling, information storage, catalysis, etc. [101, 107-109]. Magnetic NPs can be easily synthesized by using wet chemical processes in aqueous systems, but there is a disadvantage; the difficulty of making a stable dispersion of these NPs for use in aqueous environments or biological systems. To resolve this restriction, a silica-coating on the magnetite core NPs offers excellent dispersion and improved biocompatibility [110]. More recently, magnetic NPs formed from different core and shell magnetic materials have been reported [111]. These unique core@shell structures allow the magnetic properties of the resulting assembly to be more precisely tuned through the choice of magnetic materials and the dimensions of the component parts.

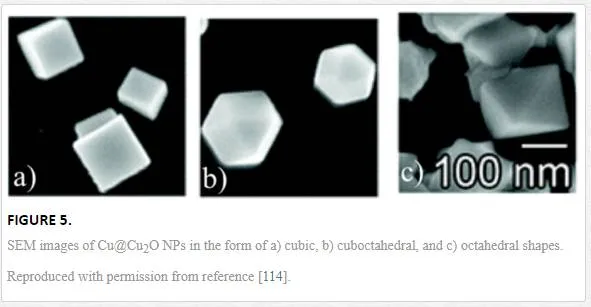

Other Forms of Core@Shell Nanoparticles. Various shaped core@shell NPs have proven to be similarly important in research because of their potential applications in the fields of catalysis [112], nanoelectronics [113], information storage [114], and sensors [115]. To synthesize these variously shaped core@shell NPs, researchers have employed a soft or hard core NP template particle to establish the physical shape [116, 117]. The most familiar examples are the use of a firm core NP of a specific shape as the template. Therefore, a soft shell material on a rigid core NP is deposited evenly to present a core@shell NP resembling the shape of the template core. Researchers synthesize core NPs through careful control of the reaction parameters, a process that relies upon controlled crystal growth using surfactants to manipulate the resulting structure [113, 116]. Examples of the types of shapes that can be made (cubic, cuboctahedral, and octahedral) are shown in Figure 5 [113]. These specific examples are Cu@Cu2O NPs and such shaped NPs can be synthesized on a similarly formed core by electro-deposition with a free capping agent.

The fitness of the coating of the shell material can be impacted by the shape of the core NP or the nature of the materials used. This means that the production of a uniform coating might be reduced with shape distortions from spherical or when the material used to form the shell reacts with the core material [118]. In the case of the octahedral gold@platinum NPs, the shell material is incompletely coated on the octahedral core because there is an incomplete reduction of the salt by the core material. Additionally, in some bimetallic “core@shell” structures, the shell is formed by a reduction-transmetalation process which fails to produce a distinguishable shell [119]. On the other hand, with the example given above, a spherical core can be more completely coated with a shell material due to a more perfect reduction of the salt and a more uniform exposure of the metal core surface in solution. These examples highlight the importance of the choice of materials used to prepare core@shell composite NPs.

Smart, multi-responsive Core@Shell nanoparticles

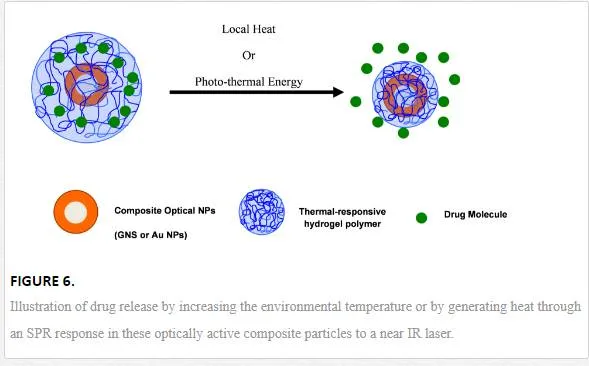

The development of a stimuli-responsive composite nanoparticle requires an efficient trigger mechanism. One such trigger is the heat generated by the light absorption of metal nanostructures. The optical properties of GNSs can be specifically controlled to maximize the absorption/scattering of light in the wavelength range of 700 to 1000 nm [64, 83]. This is advantageous because light at wavelengths between 800 nm and 1200 nm, a range called the “water window”, can penetrate human tissue, enabling its use in biomedical applications [59]. Several studies have pursued the use of this technology in combination with mesoporous silica shells that can carry model drugs. This drug carrying capacity exists in part because of the large pore volume in the etched silica surface, a feature that is tunable to achieve a specific mesopore diameter (2-50 nm). However, mesoporous silica nanoparticles by themselves are not “smart” materials because these NPs cannot release drugs in a precise and controlled manner at a specific location (i.e., they have irreversible pore openings). To overcome this drawback, our research group has explored the growth of a stimuli-responsive hydrogel polymer coating on gold nanoshells that can release a model drug upon the collapse of the hydrogel matrix. These hydrogel polymers are very useful materials in a variety of applications such as drug delivery, chemical separations, and catalysis. But such polymers need an appropriate stimulus to initiate the release of a drug remotely. For many hydrogel applications, heat is used to initiate the collapse of the polymer hydrogel. Since specific frequencies of light can be used to generate heat at the surface of GNSs that are responsive to such light, the combination of a well-tuned nanoshell for specific light absorption and a thermally-responsive hydrogel provide the potential for remotely controlled drug delivery, a smart, multi-responsive core@shell nanoparticle system.

Additionally, core@shell composite particles that respond to magnetic stimuli can also be used to perform useful tasks in controlled drug delivery [77, 78], bio-separation [120], chemical catalysis [121, 122], and electronics [1, 3]. By integrating the application of both their physical and chemical properties, these magnetic core@shell materials can become multifunctional devices that enable a variety of advanced applications that cannot be accomplished by simple magnetic NPs alone. Recent examples of the application of magnetic NPs in research have demonstrated their usefulness because of their capacity to produce heat under an external oscillating magnetic field or to be manipulated remotely, allowing for their use as an anti-tumor treatment, cell tracking tag, or drug delivery vehicle [123-125]. These core@shell composite particles that respond to both a magnet and other external stimuli, typically consist of a magnetic core encapsulated in a stimuli-responsive hydrogel copolymer layer that responds rapidly to changes in temperature slightly above that of the body. And such a coating heightens the particles’ biocompatibility and chemical stability in an aqueous medium [126-138].Core@shell composite particles that respond to optical, magnetic, and other external stimuli (e.g., temperature, ionic strength, and pH), can be used to perform more useful tasks in research. For this project, we employed a biocompatible mesoporous silica interlayer between the magnetic core and the hydrogel copolymer outer layer to improve the composite particle’s loading capacity and payload release effectiveness. The advantages that such porous structures provide is their high surface area (ca. 1000 m2/g), large pore volume (ca. 1 cm3/g), tunable mesopore diameter (2-50 nm) and biocompatibility [139, 140]. Thus, impregnation of these mesoporous silica and poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-acrylic acid; NIPAM-co-AAc)-coated magnetic NPs (or gold GNSs as the core) with drugs produces a nanoscale drug-delivery system that can be specifically targeted and magnetically (or phothermally) activated. We call them “smart” core@shell NPs.

Synthesis of smart multi-responsive Core@Shell nanoparticles

To accomplish the research goals described above, hydrogel-based core@shell composite NPs were fabricated by encapsulating a mesoporous silica-coated GNS (or Fe3O4 NP) as the core with a PNIPAM-co-AAc copolymer coating [141]. The oleylamine-functionalized mesoporous silica-coated GNS (or Fe3O4 NP) was used as a nano-template for the shell layer growth of a hydrogel copolymer. Ammonium persulfate (APS) was used as a polymerization initiator to produce a hydrogel-encapsulated composite NP. The amount of NIPAM monomer was optimized for the hydrogel-encapsulated mesoporous silica-coated composite NPs [142]. The shell layer thickness was increased with an increase in polymerization time until no further increase in the shell layer thickness was clearly observed [143]. Hydrogel-encapsulated mesoporous silica-coated composite NPs exhibited systematic changes in particle size corresponding to the variation of temperature, which originates from hydrogen-bonding interactions between PNIPAM amide groups and water, as well as electrostatic forces attributed to the ionization of carboxylic groups in the acrylic acid.

Long term research objectives

Lee and co-workers recently reported the initial methodology to precisely control drug delivery by employing gold NPs and GNSs coated with a pH- and temperature-responsive hydrogel originating from the co-polymerization of NIPAM and acrylic acid [142-144]. These nontoxic composite NPs were designed to be loaded with drug molecules, providing the ability for the NP cores to be photothermally activated, initiating collapse of the hydrogel coating and releasing the drug molecules, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Furthermore, we have been working to employ a mesoporous silica interlayer between a gold-coated silica core and a hydrogel outer layer to prevent unwanted structural changes to the gold shell during photomodulation and to assist in the carrying of hydrophobic or hydrophilic drugs to targeted sites [141]. The advantages that such porous structures provide is their high surface area (ca. 1000 m2/g), large pore volume (ca. 1 cm3/g), tunable mesopore diameter (2-50 nm) and biocompatibility [139, 140]. By using smart hydrogel technology as an outer layer and a mesoporous silica coating as an interlayer, GNSs that are activated by tissue-transparent near-IR light can be more effectively used for advanced medicinal applications. With our initial investigation, once these nontoxic composite NPs were loaded with methylene blue (MB; a dye used as a model drug), and the NPs thermally activated, the hydrogel coating collapsed and released the test molecules. The potential for such smart, multi-responsive core@shell nanoparticles for use as drug delivery carriers, contrast agents, and therapeutic entities will clearly encourage the application of this new technology in future research projects.