Posted inMaterial Science

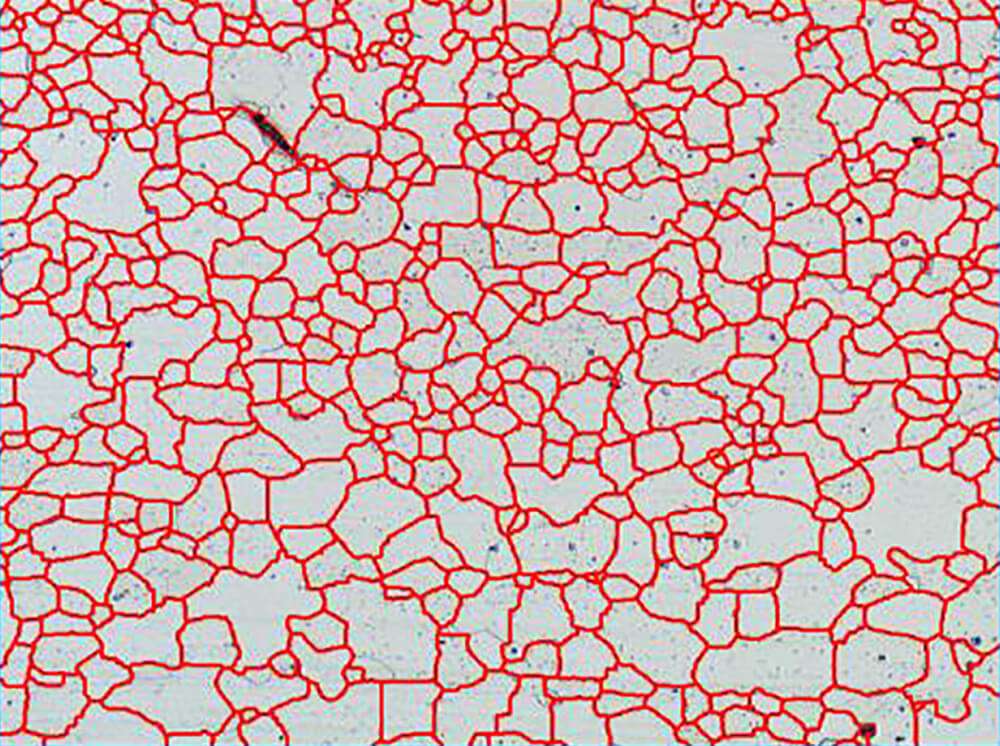

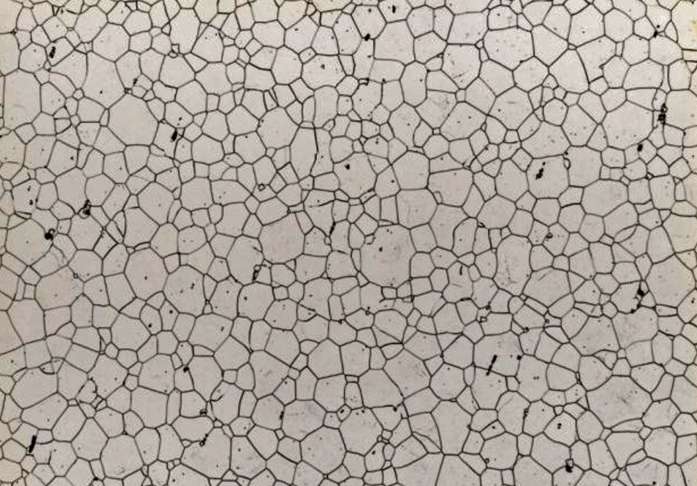

Development of microstructure in eutectic alloys

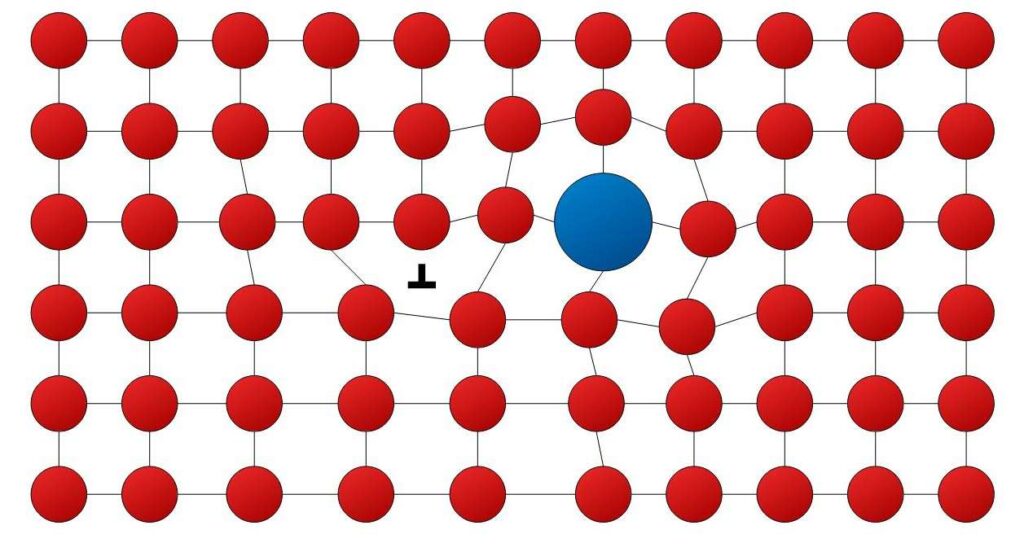

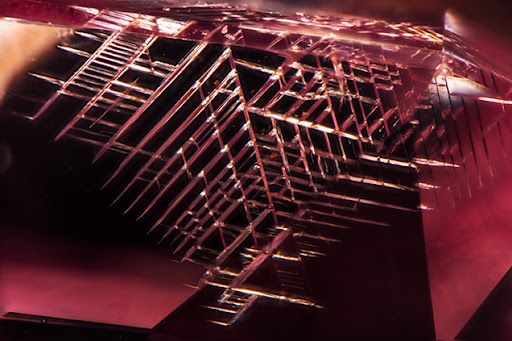

Case of lead-tin alloys, A layered, eutectic structure develops when cooling below the eutectic temperature. Alloys which are to the left of the eutectic concentration (hipoeutectic) or to the right (hypereutectic) form a proeutectic phase before reaching the eutectic temperature, while in the solid + liquid region. The eutectic structure then adds when the remaining liquid is solidified when cooling further. The eutectic microstructure is lamellar (layered) due to the reduced diffusion distances in the solid state. To obtain the concentration of the eutectic microstructure in the final solid solution, one draws a vertical line at the eutectic concentration and applies the lever rule treating the eutectic as a separate phase.