Posted inMaterial Science

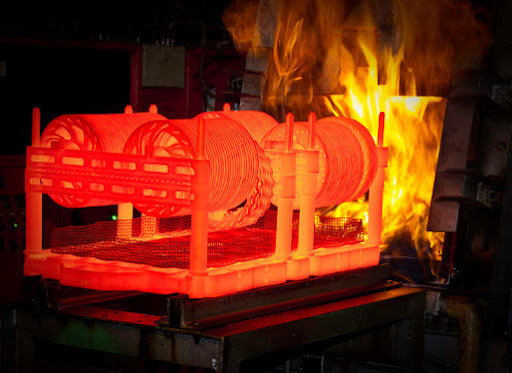

Tempering

Is a process done subsequent to quench hardening. Quench-hardened parts are often too brittle. This brittleness is caused by a predominance of Martensite. This brittleness is removed by tempering. Tempering results in a desired combination of hardness, ductility, toughness, strength, and structural stability. Tempering is not to be confused with tempers on rolled stock-these tempers are an indication of the degree of cold work performed. The mechanism of tempering depends on the steel and the tempering temperature. The prevalent Martensite is a somewhat unstable structure. When heated, the Carbon atoms diffuse from Martensite to form a carbide precipitate and the concurrent formation of Ferrite and Cementite, which is the stable form. Tool steels for example, lose about 2 to 4 points of hardness on the Rockwell C scale. Even though a little strength is sacrificed, toughness (as measured by…