Posted inMaterial Science

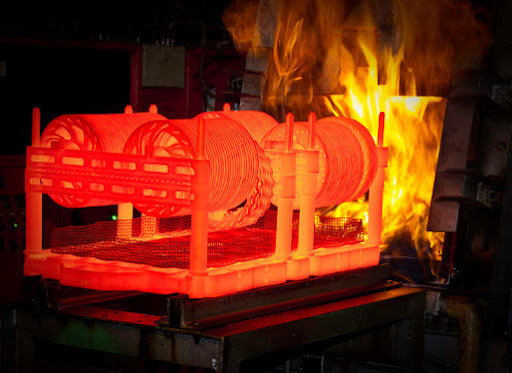

Case Hardening

Case hardening produces a hard, wear-resistant sur- face or case over a strong, tough core. The principal forms of casehardening are carburizing, cyaniding, and nitriding. Only ferrous metals are case-hardened. Case hardening is ideal for parts that require a wear-resistant surface and must be tough enough interally to withstand heavy loading. The steels best suited for case hardening are the low-carbon and low-alloy series. When high-carbon steels are case hardened, the hardness penetrates the core and causes brittleness. In case hardening, you change the surface of the metal chemically by introducing a high carbide or nitride content. The core remains chemically unaffected. When heat-treated, the high-carbon surface responds to hardening, and the core toughens.