Marketing planning involves objectives and plans with a 2-5-year time horizon and is thus further from day-to-day activity of implementation. Because of their broader nature and longer-term impact, plans are typically developed by a combination of higher level line managers and staff specialists. If the specialists take over the process, it loses the commitment and expertise of the line managers who are responsible for carrying out the plan. The planning process is probably more important than the final planning document. The process ensures that a realistic, sensible, consistent document is produced and leads to important organizational learning and development in its own right.

Marketing Programming, Allocating and Budgeting

This part of the marketing process involves a good deal of detail and focuses generally on the one-year time horizon.

Programs can be related to either one element of the marketing mix such as distribution for one or more products or to all elements of the mix for a single product or market. To some extent, the choice will be determined by the nature of the company’s organization. The more functional the organization (i.e. separation of marketing functions such as advertising, sales, etc.), the more likely it is that the programs will focus on one aspect of the mix across all products and markets. On the other hand, companies which organize around products or markets tend to also develop programs for each of them.

Allocating is a necessary function because there is never enough of any scarce resource such as advertising budget or distribution effort to meet the ‘needs’ of all products, markets and programs. In many ways, marketing is deciding what not to do: which prospects not to sell to, which products not to produce to, etc. Allocation is the formal process of choosing what to do and what not to do, as well as choosing how much to do. Because marketers tend to be optimists, they often underestimate the amount of effort which will be required to accomplish a goal. Allocation requires the stark realism to separate the clearly feasible from the hopeful. It forces the marketer to set explicit priorities and to make hard decisions.

Budgeting reflects the programs and allocations in a set of quantitative forecasts or estimates which are important within and beyond the marketing function. The budgets generally include financial proform as which are used by the control and finance functions to forecast cash flows and needs. They also generally include unit sales forecasts which are used by production scheduling personnel to ‘load the factory’ or service operation. If the forecasts are too low, customer needs are unmet, and sales are lost. If the forecasts are too high, capacity sits idle and costs are much higher than they should have been.

Marketing Implementation

Strategy formulation, marketing planning, and programming, allocating and budgeting all lead to marketing implementation as shown in Figure .This is the execution phase which, in part produces the actual results. Poor implementation can ruin even the best strategies, plans and programs. The total purpose of all that goes before implementation is to ensure excellent execution.

Implementation means different things to different people in the organization. To the salesperson, it means going through all of the steps of the selling process, while to the sales manager, it might mean reorganizing the whole sales force. Because of the relatively short time frame involved in most implementation activities, monitoring and auditing are generally easier than for the longer-term strategies and plans. Implementation is very people-oriented. The results of implementation are manifested in people doing things – buying, selling, training, reorganizing, etc. Marketing implementation is unique compared to implementation in most other functional areas because the primary focus of marketing is outside the company. Thus marketing implementation focuses on prospects, customers, distributors, retailers, centres of influence (who are the influencers in a buying decision – they specify but do not purchase). But marketing implementation also includes dealing with other functional areas to gain support and to develop coordination. For example, product managers must implement their plans and programs through product development, production, service and logistics personnel in other functional areas.

Marketing implementation involves a very interesting tension between the structures the firm puts in place to guide marketing efforts and the skills of the managers doing the marketing job. In most firms, what happens is that over time the structures become rigid and dysfunctional to changing marketplace needs, which guides the firm to destinations it does not want to reach! It is only by the timely intervention of the marketers, using their personal skills to ‘subvert the organization toward quality’ that good marketing actions result.

Monitoring and Auditing

One reason to develop plans, programs and budgets is to have a set of goals or standards against which to measure performance. Marketing audits usually include two parts. The first is an assessment of performance against quantitative goals. The second part of a comprehensive audit reviews the processes and other non-quantifiable aspects of the marketing operation. Because marketing is a mixture of art and science, quantitative and qualitative, and because it involves so many interactive variables, it is hard to audit. Standards are few and comparisons are difficult.

The audit raises a variety of important topics:

1. Who should perform the audit? Can the planners, programmers and executors audit their own performance without bias? If they cannot, who knows enough about the operation to perform the audit? Should outsiders such as consultants be involved and in what capacity?

2. How often should the audit be performed? Should it be on a regular basis or only at certain important points?

3. How comprehensive should the audit be? Should it involve all aspects of marketing or just some?

While auditing normally refers to an activity which is done only on certain occasions, monitoring generally refers to a more day-to-day review activity. It also often refers more to a review of external data than internal activities. It, too, is an important part of the total marketing process because it provides a frequent check of progress against plans and programs.

Analysis and Research

All marketing decisions should be based upon careful analysis and research. The analysis and research need not be quantitative, but it should be deliberate and should be matched to the magnitude of the decision being made. While formal analysis and research are important, nothing replaces common sense and good judgment. The marketer’s kit has some very powerful analytical tools and the rapid development of decision support systems, mathematics including statistics, and other supporting disciplines such as psychology and sociology insure that the diversity and power of the tools will continue to increase. All of the tools must be applied carefully and intelligently to the decision at hand. It is a fine line, indeed between healthy scepticism and arrogant neglect of useful tools. The right analytical tool well applied can substantially improve marketing decision making.

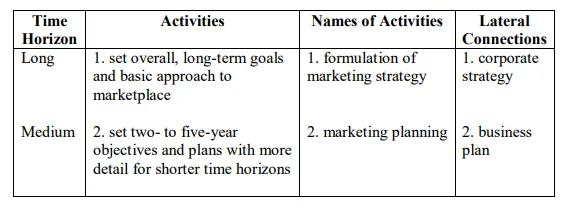

Below Table has two dimensions. The first is temporal – it shows the natural development from strategy formulation through planning, programming, allocating and budgeting on to implementation. This process is not nearly as ‘clean and separated’ as the table implies. The activities are interrelated and contemporaneous. The second dimension is the lateral connection to other functional parts of the organization, such as production and operations, finance, control and human resources management. Each step has a company or business counterpart in the right-hand column. The marketing strategy thus becomes part of the total corporate strategy, which includes all functional areas. The marketing plan is often part of a broader corporate business plan. The marketing plan is usually the ‘front end’ of the corporate plan, because it spells out the operation, human and financial resources needed to support the organization’s approach to its markets.

Table Activities and Lateral Connections

Marketing programs and budgets are usually part of the organization’s fundamental operating documents. For example, the sales forecasts in the programs and budgets become the production schedule for the manufacturing function. Those, in turn, become the staffing programs for the human resource function and indicate the working capital needs to be supported by the financial function. If finance cannot support such a high level of inventory and accounts receivable, the sales forecast, production schedule and staffing program must be scaled down. In most organizations, great effort must be devoted to such lateral connections. The coordination needs are very high and the amount of conflict often great. Risk aversion and opportunity sensitivity differ among functions. Varying reward systems sometimes encourage different types of behaviour. The organization must develop formal and informal ways to foster good, open lateral connections.

Schematic of Marketing Process

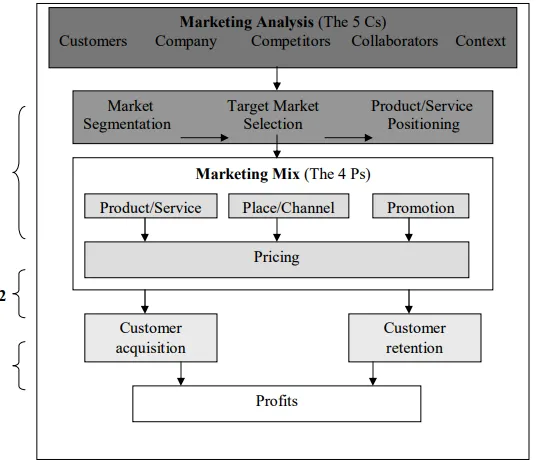

Figure represents a schematic describing a general process of marketing strategy development. As shown, five major areas of analysis (5 Cs) underlie marketing decision making – customers, company, competitors, collaborators and context. The questions to raise in each of these areas are:

· Customer needs – What needs do we seek to satisfy?

· Company skills – What special competencies do we possess to meet those needs?

· Competition – Who competes with us in meeting these needs?

· Collaborators – Who should we enlist to help us and how do we motivate them?

· Context – What environmental (say, cultural, technological or legal) factors limit what is possible?

This leads first to specification of a target market and desired positioning and then to the marketing mix (4 Ps). This results in customer acquisition and retention strategies driving the firm’s profitability. In this schematic, value creation happens by identifying target segment, establishing a product/service positioning and developing the suitable product, place (distribution) and promotion for the chosen market segment. The pricing decision helps to capture value – for the company and for the customer. Value is sustained by acquiring and retaining the customers at a profit for the firm.

Figure; Schematic of marketing process