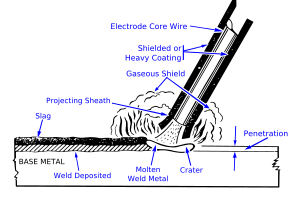

Shielded metal arc welding (SMAW), also known as manual metal arc (MMA) welding or informally as stick welding, is a manual arc welding process that uses a consumable electrode coated in flux to lay the weld. An electric current, in the form of either alternating current or direct current from a welding power supply, is used to form an electric arc between the electrode and the metals to be joined. As the weld is laid, the flux coating of the electrode disintegrates, giving off vapours that serve as a shielding gas and providing a layer of slag, both of which protect the weld area from atmospheric contamination.

Because of the versatility of the process and the simplicity of its equipment and operation, shielded metal arc welding is one of the world’s most popular welding processes. It dominates other welding processes in the maintenance and repair industry, and though flux-cored arc welding is growing in popularity, SMAW continues to be used extensively in the construction of steel structures and in industrial fabrication. The process is used primarily to weld iron and steels (including stainless steel) but aluminium, nickel and copper alloys can also be welded with this method.

Schematic illustration of the shielded metal-arc welding process

Operation

To strike the electric arc, the electrode is brought into contact with the workpiece in a short sweeping motion and then pulled away slightly. This initiates the arc and thus the melting of the workpiece and the consumable electrode, and causes droplets of the electrode to be passed from the electrode to the weld pool. As the electrode melts, the flux covering disintegrates, giving off vapours that protect the weld area from oxygen and other atmospheric gases. In addition, the flux provides molten slag which covers the filler metal as it travels from the electrode to the weld pool. Once part of the weld pool, the slag floats to the surface and protects the weld from contamination as it solidifies. Once hardened, it must be chipped away to reveal the finished weld. As welding progresses and the electrode melts, the welder must periodically stop welding to remove the remaining electrode stub and insert a new electrode into the electrode holder. This activity, combined with chipping away the slag, reduce the amount of time that the welder can spend laying the weld, making SMAW one of the least efficient welding processes. In general, the operator factor, or the percentage of operator’s time spent laying weld, is approximately 25%.

The actual welding technique utilized depends on the electrode, the composition of the workpiece, and the position of the joint being welded. The choice of electrode and welding position also determine the welding speed. Flat welds require the least operator skill, and can be done with electrodes that melt quickly but solidify slowly. This permits higher welding speeds. Sloped, vertical or upside-down welding requires more operator skill, and often necessitates the use of an electrode that solidifies quickly to prevent the molten metal from flowing out of the weld pool. However, this generally means that the electrode melts less quickly, thus increasing the time required to lay the weld.

Application

Shielded metal arc welding is one of world’s most popular welding processes, accounting for over half of all welding in some countries. Because of its versatility and simplicity, it is particularly dominant in the maintenance and repair industry, and is heavily used in the construction of steel structures and in industrial fabrication. In recent years its use has declined as flux-cored arc welding has expanded in the construction industry and gas metal arc welding has become more popular in industrial environments. However, because of the low equipment cost and wide applicability, the process will likely remain popular, especially among amateurs and small businesses where specialized welding processes are uneconomical and unnecessary.

SMAW is often used to weld carbon steel, low and high alloy steel, stainless steel, cast iron, and ductile iron. While less popular for nonferrous materials, it can be used on nickel and copper and their alloys and, in rare cases, on aluminium. The thickness of the material being welded is bounded on the low end primarily by the skill of the welder, but rarely does it drop below 0.05 in (1.5 mm). No upper bound exists: with proper joint preparation and use of multiple passes, materials of virtually unlimited thicknesses can be joined. Furthermore, depending on the electrode used and the skill of the welder, SMAW can be used in any position.