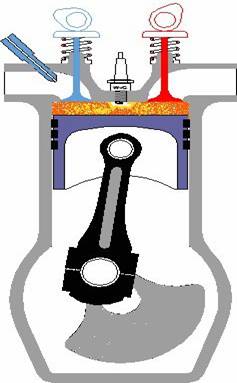

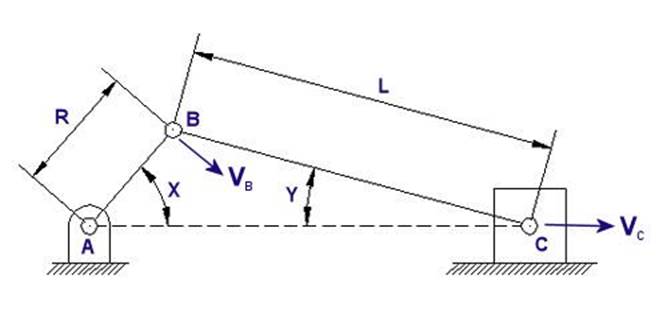

When we refer to the study of the kinematics of machines, we’re referring to the relationship between machine parts and how those parts behave as they move through their ranges of motion. What this means is that there is particular concern with the relative motion of machine parts, that is, how they relate to each other, their position, distance, velocity, and acceleration. When speaking of the kinematics of machines, a mechanism is considered to be like a chain with a system of links that are connected together. This chain is constrained, meaning that independent movement of one part is not possible. These parts are interconnected, and they all move relative to each other. Motion in any one link of this kinematic chain will result in a relative and predictable motion to each of the others. Now, by “chain,” I don’t necessarily mean a chain in the physical sense, but rather the fact that the parts of the mechanism are linked together. To illustrate what I’m talking about, let’s consider the gasoline engine shown in Figure 1 below.  Figure 1To help you follow along, let’s turn the engine on its side and name the parts of one of its kinematic chains. This is shown in Figure 2. Figure 1To help you follow along, let’s turn the engine on its side and name the parts of one of its kinematic chains. This is shown in Figure 2.  Figure 2 Suppose you want to analyze how fast the engine’s piston is moving at any given instant during its operation. Suppose further that you know how fast the crank shaft is turning. Where would your analysis begin? Well, while studying the motions of machine parts, it’s helpful to draw the parts first in skeletal form so that only those dimensions that affect their motions are considered. Let’s represent the kinematic chain of Figure 2 in skeletal form. See Figure 3 Figure 2 Suppose you want to analyze how fast the engine’s piston is moving at any given instant during its operation. Suppose further that you know how fast the crank shaft is turning. Where would your analysis begin? Well, while studying the motions of machine parts, it’s helpful to draw the parts first in skeletal form so that only those dimensions that affect their motions are considered. Let’s represent the kinematic chain of Figure 2 in skeletal form. See Figure 3  Figure 3 Lastly, we embellish the skeleton with the depiction of angles that are at play as the parts of our engine move, and we add the relevant symbols that will allow us to build the equations we’ll be working with. This is shown in Figure 4. Figure 3 Lastly, we embellish the skeleton with the depiction of angles that are at play as the parts of our engine move, and we add the relevant symbols that will allow us to build the equations we’ll be working with. This is shown in Figure 4. Figure 4 So, as the engine runs, the crank AB rotates around the center of the crank shaft A. The connecting rod BC is attached to the piston at the wrist pin C. The piston moves back and forth as AB rotates. Now here is where things get a little hairy, and for some of you it may look somewhat like code or a foreign language. The tangential velocity VB of the crank pin B is shown in Figure 4 as a vector. A vector is something which depicts both a magnitude and direction. And since VB is a “tangential velocity,” it is moving in a direction which is at a right angle, that is, at a 90-degree angle in relation to the crank AB. This relationship will always exist between VB and the crank AB. In the posed scenario, VB is a velocity, so let’s say its magnitude will be in units of inches per second. The magnitude of the vector VB is then directly related to the speed of crankshaft AB and is determined by this equation:VB = 2∏RN ÷ 60 Referring to Figure 4, R is the distance between the center of the crank shaft and the center of the crank pin in inches. N is the rotational speed of crank AB in revolutions per minute (rpm). If one knows the crank angle X, the crank length R, and the connecting rod length L in Figure 4, they can then use trigonometry to determine the velocity of the piston. This velocity is represented by the vector VC, and its magnitude, or value, would be found by using the following equation…VC = [VB] × [sin(X + Y)] ÷ [sin(90° – Y)]…where the angle Y is found by:Y = [sin-1(R ÷ L)] × [sin(X)] Analysis of kinematics of machines would become even more complicated when complex mechanisms like oddly shaped linkages, cams and followers, and gear trains are involved. Figure 4 So, as the engine runs, the crank AB rotates around the center of the crank shaft A. The connecting rod BC is attached to the piston at the wrist pin C. The piston moves back and forth as AB rotates. Now here is where things get a little hairy, and for some of you it may look somewhat like code or a foreign language. The tangential velocity VB of the crank pin B is shown in Figure 4 as a vector. A vector is something which depicts both a magnitude and direction. And since VB is a “tangential velocity,” it is moving in a direction which is at a right angle, that is, at a 90-degree angle in relation to the crank AB. This relationship will always exist between VB and the crank AB. In the posed scenario, VB is a velocity, so let’s say its magnitude will be in units of inches per second. The magnitude of the vector VB is then directly related to the speed of crankshaft AB and is determined by this equation:VB = 2∏RN ÷ 60 Referring to Figure 4, R is the distance between the center of the crank shaft and the center of the crank pin in inches. N is the rotational speed of crank AB in revolutions per minute (rpm). If one knows the crank angle X, the crank length R, and the connecting rod length L in Figure 4, they can then use trigonometry to determine the velocity of the piston. This velocity is represented by the vector VC, and its magnitude, or value, would be found by using the following equation…VC = [VB] × [sin(X + Y)] ÷ [sin(90° – Y)]…where the angle Y is found by:Y = [sin-1(R ÷ L)] × [sin(X)] Analysis of kinematics of machines would become even more complicated when complex mechanisms like oddly shaped linkages, cams and followers, and gear trains are involved. |

Posted inStrength of Materials